A Musician’s Guide to Navigating the Next Pandemic (an essay)

by Ian Howell

8 March 2021

The coronavirus pandemic of 2020-21 was terrible for musicians. In lives cost, in lives altered, and in the cultural atrophy when the practice of music is put on hold. One hopes the next pandemic occurs so far in the future that this essay will be as relevant then as one written in 1917 would be today. I suppose one hopes that the next time this happens, vaccines will be custom prepared in vending machines and instantly available; that this was the last pandemic. Some general advice about how to think about this sort of crisis bears writing down though, in case we are as unlucky then as now. I actually write this with hope in my mind, as I think it is highly likely that the fall of 2021 will bear more resemblance to 2019 than it will to 2020.

This essay will suggest how to recognize challenges as they happen, to define your own values, and to take actions. Please do not use it as a check list for how you managed this pandemic. No one managed this one well. This essay is for the next pandemic. The main ideas covered are: (1) recognize the time horizon early on, (2) make financial plans according to a realistic rather than optimistic time scale, and seek relevant and trustworthy expertise, (3) recognize the cost of inaction, (4) define your values, hold to them, remain open to solutions you do not currently have, and recognize your ability to grow.

Time horizon

We thought this would end quickly.

It did not.

If we had acted from the start

like this was going to last as long as it did,

we would have made different choices.

In perception research there is a concept called a just noticeable difference (JND). Humans are bad at granular analysis. Our sensory systems have resolution limits. One may not be able to tell the difference between 32 and 32.5°F, for example. Or the difference between 1,000 Hz and 1,000.005 Hz. Somewhere between those small variations and a temperature swing of 40° or pitch change of a fifth lies the just noticeable difference: the change that is just big enough that you notice it. The JND for waiting out a natural disaster appears to be about two weeks. Anyone paying attention to public messaging prior to March 13th 2020 would have noticed this two week horizon offered as a reasonable amount of time to wait-and-see.

The messaging outliers—the ones that do not game the JND—are where to look. As of March 6th governments were still suggesting we wait to get more information. Those actually responsible for either facilitating or preventing gatherings acted as though they had enough information. The SXSW festival was cancelled. Stanford had moved classes online. Cornell shut down its campus. Both Harvard and MIT announced international and domestic travel bans with expiration dates months in the future. The Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston announced a similar ban, notably with no expiration date—it is still in effect today. That day, Boston hospitals publicly announced that they were breaking into their mass disaster supply warehouses.

Publicly, those interested in preserving calm suggested we wait two more weeks to see how things developed. The problem was the two week window restarted each morning. By the beginning of May, when a panelist mentioned on a National Association of Teachers of Singing webinar that it may be years before we could safely sing as we did before, the ever advancing two week waiting periods made brutal honesty feel like the bottom dropped out. All along, those actually responsible for institutional liability and medical care had told us to shut it down; that a vaccine would be a year or more away with a moonshot approach.

For the next pandemic, it is important to know when you are being comforted by an authority figure who may not even be in charge in a year, versus when you are called to action by someone who understands the dangers of the situation. Do not be fooled into thinking that the answer is the one you prefer or that it lies somewhere between extremes. If someone tells you to check back in two weeks, that is code for, “we don’t know anything and would prefer you stay calm.” That is not the same as, “this will be better in two weeks.” If someone credible says this might last years, start to plan as though that will happen.

Planning financially and evaluating experts

Budgets are credos.

They are statements of belief.

They are declarations of personal and institutional values.

At best we give advice based on our experience.

At worst we give advice to justify our own choices.

First, money is real, the pandemic decimated livelihoods, and your value as a teacher, musician, or human is not tied to your ability to either access or afford any given piece of technology or education. If you survived, you survived, and nothing matters more than that.

With the gift of perfect foreknowledge, all of us could have made the perfect tech and education investments to facilitate what was needed to continue making or teaching music. Or even to expand beyond what we had been able to offer. Since we did not have perfect foreknowledge, it became crucial to figure out who to trust. The most important characteristics to look for in an expert are that important knowledge is shared freely, mistakes are acknowledged, conflicts disclosed, and that they adapt to new information as it is revealed even if it is inconvenient to their business model. If someone tries to take your money by selling you a worldview—by dismissing options they have not used, or by oversimplifying without explaining the value of understanding complexity—they are trying to sell you what they know, rather than what can be known.

Compared to the question of whether to trust politicians or medical professionals, the question of who to listen to about microphones or apps seems provincial. However, there are four ideas to keep in mind when evaluating an information source. These suggestions do not just point to accurate and truthful information. More important is the question of whether the source has sufficiently comprehensive knowledge and whether their suggestions meet your needs. An expert opinion can be accurate but also too narrowly focused to be helpful. A helpful solution can be incomplete.

(1) Has this person considered your use case specifically? The same solution can be perfect for one use case and overkill for another. There are many ways to interact with and use microphones, for example. An audio engineer is likely to attempt to approximate the values of a recording studio. Someone interested in teaching a music lesson may find that those recommendations artificially improve the sound of the instrument as it is in the room. A teacher may want to hear sounds unwanted on a record. Your use case may involve musical instruments that are significantly louder than others. A mic that works for a harp may not work for a snare drum. Or your use case may require musical collaboration, which impacts both software and hardware choices.

(2) Is the person aware of the limitations of their suggestions? A high latency usb microphone, for example, may be attractive for a number of applications, but extremely limiting if one wants to shift toward using low latency transmission apps or upgrade later. Be cautious if the person making recommendations does not take the time to explain the downside of a given choice.

(3) Does the person have broad knowledge of the type of technology they are recommending? My hope is that dissertations will be written on the “Blue Yeti Effect” in coming years. Somehow, the music education industry decided that the Blue Yeti USB podcasting microphone was indicated for taking or teaching online lessons. Numerous people pushed this microphone publicly, and scores of others parroted the recommendations. I think the two upsides for this microphone are that it makes speech sound warm and full like a radio broadcaster if you are close, and it feels heavy when you hold it. Otherwise it is a terrible (and expensive) microphone for many applied music lesson use cases. Whenever someone recommends a piece of technology like this, the next question should be, how many other microphones have you tried? The Blue Yeti was not recommended because it is good. The Blue Yeti was recommended because it is what a group of educators were aware of. The fact that they had not held other options in their hands and had not compared those other options to the Blue Yeti moderates the recommendation. This is a roundabout way to say, at all times be clear who is backstopping the information you receive. Does that person have relevant experience?

(4) Be aware of their business model. There is nothing wrong with charging money for knowledge or services. But notice where the value is. If the person creates their value by promising the answers lie behind a firewall, be suspicious. If the value they generate is that they save you from Zoom, but not in the way you need, be careful not to embrace a bad solution to your problem. If the person is selling a piece of software, be skeptical of their critiques of competitors. They may be right, they may not be. But they have a conflict of interest.

We do not need to be experts ourselves. But in the next pandemic, do not discount your ability to evaluate information about music technology. Do not divide the music world in to experts/pioneers and lay people/consumers and marginalize what you are capable of. The critical listening and critical thinking skills needed to teach music will serve you here. You can tell when something does not sound good enough. Trust yourself. Have hope that you can engage these questions instead of simply accepting a solution that does not meet your needs. Have hope that you can discern what your needs are.

The Cost of Inaction

Every choice costs someone something.

If in March of 2020 we had known the music business would return to normal in two weeks, only a fool would have invested in good equipment or taken the time to learn new software. If everyone had to switch to online experiences for three months, it would be a waste of time to think through the relative merits of cheap versus nice equipment. It has been 360 days since the Northeast United States closed down. It will easily be another three to six months before regular citizens will have equal access to a vaccine, and at that point we start the process of inching back toward a more open society. This is playing out exactly like the public health officials told us it would in March and April of 2020. Long enough and deadly enough that it would permanently affect the world. Not so long, and not so deadly that it would end our civilization. Yet we held onto the hope that everything would return to normal quickly, despite the mountain of evidence that it would take years. Because of how long this has already lasted, those who acted created both ongoing streams of revenue and opportunities for their communities, and were also able to explore completely unheard of solutions. Those who waited for everything to return to normal have had a much harder time.

Again, money is real and anyone reading this who has faced significant hardships, please know this is not about your choices. This essay is not even about this pandemic. This one is done, and our failures and successes are baked into history at this point. But many—especially institutions—with the means to invest in the way that would make sense to prepare for a one to two year long interruption, chose not to. Many who could have laid out for their students the advantages of incremental technological improvements chose not to. Teachers with students already paying tens of thousands of dollars per year in tuition decided that the last $15 for an ethernet cable, or $25 for a dongle was the thing they were unwilling to require. Institutions that could have innovated retreated instead, perhaps comforted by sufficient enrollment regardless of whether the education was of quality. Broadly, we hid behind the idea that we had to meet students where they were as though that obviated our responsibility to bring information, material support, and solutions to that meeting.

The knock on effect almost a year later is that large numbers of musicians and teachers had a year that did not equal what in person education would have provided. I know this is true because only a small percentage of students remotely auditioning for college and graduate school programs this season knew how to optimize their Zoom setups. Many were on older versions of the app that lacked important features, they did not understand how to optimize what they had, and they had not practiced with the technology. One can absolutely listen past these issues. But this means that their teachers had likely been listening past them as well for a year. This is a cost that must be balanced against any other cost. Perhaps in the grand scheme of things it does not matter. I have to think that better is better. That there is value in improving what can be improved. That it is important to model this behavior for students and colleagues.

This means, if someone says that FaceTime is great for music lessons, your first reaction should be to ask, what else have you tried, what did you do to attempt to overcome technological and logistical challenges, what are the obvious limitations, and what have you done to educate yourself about optimizing either your or your student’s connection. And perhaps critically, would you endorse this solution if you knew you would be doing it for a year or more? If someone says that Zoom is fine, please keep in mind the context in which that statement is made. An app like Zoom is great for exactly what Zoom is capable of. But Zoom is not an easy app to use. Beyond the latency and audio quality issues, settings are buried and confusing for many, and the best quality features require unforced updates. The result is that good features are often missing from a student’s device. Zoom costs both money and time to function at its full potential. It is not cheaper than other solutions. FaceTime is certainly easy to use, but its auto gain control will always give a false sense of how even the intensity of a voice is. But these questions are never actually settled and these apps cannot be evaluated outside of the context of their use. There is nothing wrong with using FaceTime or Zoom. The danger is in not knowing why you are using it instead of another option. The danger is in not knowing what the convenience is costing you and in ignoring the compounding cost over time. The danger is in assuming the complex solution you know is easier than the complex solution you have not yet learned. The best solution is not always the fanciest, but knowing why you are using what you use, how to make it work well, and how to use it to meet your pedagogical goals will give you confidence in whatever solution you do use.

Define your values and remain open to what is next

Values push against limitations.

Limitations bend to values.

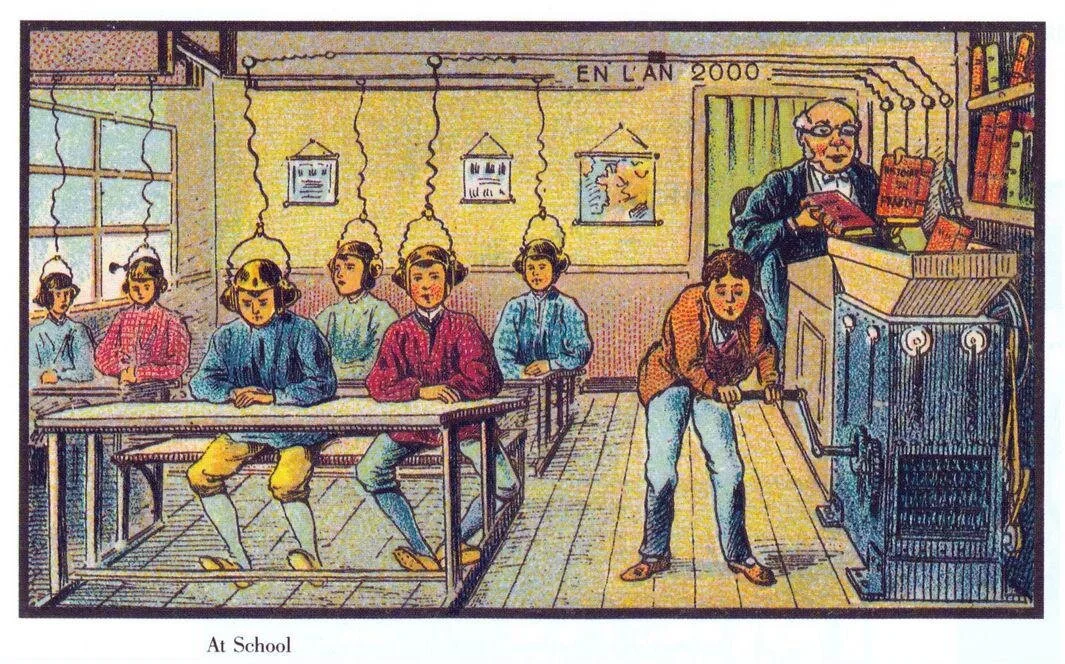

For me, limitations and constraints, and our reaction to them, frame the question at the heart of how musicians can possibly react to the challenges of a pandemic. Everyone is constrained. Even the fastest fiber optic connection with the nicest audio equipment has limitations. For that matter, the need to gather people at a specific time in a specific room in a specific physical building is a limitation and a barrier that we may not have recognized before. Your limitation may be that someone currently only has an iPad and Wi-Fi to start. In the next pandemic, perhaps we will discuss whether the NeuroCaster4200 brain implant is really worth the extra reach to Mars over last year’s model. I do not know. But there will always be a line one draws that rules certain solutions in and others out. The question is what role values—literally the things you are not willing to do without—play in determining where that line is.

We must each answer—and make peace with answering—this question: has your pedagogy now become shaped by the limitations of the technology, or are you pushing the technology to continue to accomplish the pedagogical goals you had in February 2020. Have your performance goals (or your organization’s plans) been driven by adherence to older models or have you attempted to innovate? These question must be considered in the context of the costs of both action and inaction. I am fascinated by two examples that currently illustrate this issue, and an open question of what happens next. The two examples I have in mind are: virtual choir videos and defending rather than acknowledging the limitations of Zoom. The open question concerns venturing into low latency, distributed audio and video technology as a stop gap for now, and as a persistent technology for after the pandemic. These examples likely represent archetypes of what might happen in the next pandemic.

Example: Projects that do not train musicians

Virtual choirs, where each individual performer separately records their audio and video to a sync track, and an engineer edits the files together to form a complete ensemble, took off in 2020. Educators had never pursued this kind of project in large numbers before, and my hope is that we will move beyond them quickly.

Multi-track recording can be a great experience and is a relevant skill for most musicians. It is the process that created the majority of existing recorded music. But virtual choirs are not that. They are skeumorphic approximations of a live performance, without any of the signifiers of spontaneity and interactivity that characterizes a real performance. And they take an incredible amount of time to organize and edit. If we are to train studio musicians, we should train studio musicians. This means an iterative multi track recording process, which can be accomplished remotely with online DAWs. In this process, any one musician is able to hear everything else already tracked, practice along with it, react to it, and collaboratively build the final product. Virtual choirs are not that.

Example: Not every limitation is a great chance to grow

Zoom is an incredible tool. Even given that its core design values align with corporate board rooms rather than music rooms, it is useful for musicians. And Zoom’s development team has been at least somewhat responsive to the needs of the music community, resulting in significant improvements since March 2020. There will absolutely be a similar “good enough “technology that emerges during the next pandemic. It is really up to any other option to justify further complexity by offering better features. The one bit of caution I would suggest is becoming enamored of features that were unimportant prior to the pandemic. Especially if leaning on those features locks you in to an experience that is subpar in other respects. The two significant downsides of Zoom at this moment are the incredibly high latency and the audio compression even in the high fidelity music mode. Many teachers are willing to accept these compromises in return for tools they did not use prior to the pandemic: the ability to use a whiteboard, the ability to record videos (with degraded audio), or even just a basic comfort with an app that they and their students have already learned.

We can get into a sort of Stockholm syndrome with an app like this. You know it when you find teachers discussing how great it is to be forced to listen past the limitations. That is illogical to me, as it is not necessary. Or put another way, if one wants to listen past limitations, great. But at this point almost no one is forced into doing that by the available technology. By a school administrator, yes. By one’s knowledge and skill, yes. But not by the technology itself. There are free or cheap options that sound amazing. And with a will to learn something new, even less ideal options can be optimized to be as true to life as possible. Put another way, for me, no additional feature (one step instead of two step recording, one step instead of two step login) is worth compromising the audio quality.

Again, timescale comes into play here. If we all teach online for only three months, who cares. If the next pandemic lasts two years, even one small change toward higher quality solutions per month will soon revolutionize the experience. This month headphones, next month an ethernet cable, the month after that time dedicated to learning about better apps, etc… A little bit at a time quickly snowballs into solutions with lasting impact.

What is the future? Not what colleges did this year

I wrote above, and will write again here that as of March 2021, I am very hopeful for the prospects of an evidence-based lifting of physical distancing restrictions. In the near to medium term. Just today the CDC released new guidelines permitting the vaccinated to move freely among one another without concern for masking or distancing. Total vaccinated has not cracked 10% of the US population as of today, but that number is climbing. I assume I’ll be able to return to teaching in person this fall.

How our return to one another’s air masses intersects with the work the music education community has done this year to better master online teaching technology remains to be seen. There is certainly an argument for keeping around the equipment as a fall back for snow days or when you or your student feels a cold coming on. I think that many students who now see the value in online lessons (saves parking, gas money, etc) will continue to take advantage of what can be done. I have professional voice students who will stay online using Soundjack. And I hope that the music education communities that had been 100% online before will benefit from the amazing advances that have occurred this year. But there is something to be said for asking questions about what can be different moving forward, what technology opens up for us, and what new options might come out of this time.

I think first off (1), we must say that the way the majority of North American music schools utilized technology this year is not a viable model for music education in the post pandemic world. Not enough support was provided to make sure that remote students could participate fully even given the limitations of remote education, let alone match an in-person experience. Little innovation was encouraged to find or develop the best solutions possible. Anyone who tells you that fully remote collegiate music education is the same as in person is trying to sell you something. Run. Second (2), there are absolutely things that we can do online that we cannot do in person, given the right equipment and training. This means we must foster creativity surrounding use of such technology. NEC launched its first Low Latency Artistic Project Grant this year, which awarded prizes to three technology-enabled projects that could only have happened in response to the Covid 19 era. Third (3), an incredible amount of development in real-time, distributed music making has occurred over the past year. What we were aware of last summer seems a distant, shadowy beta version of what we see now. And the next two months are going to change things even more.

What is coming? What is new? What should we be excited about? First, the SoundJack and JackTrip Virtual Studio projects are now the two most robust low latency, distributed music making projects in public use. They are different enough in terms of features to find niche user bases, but they have converged in terms of hardware. They both work on computer platforms, and also on simple Raspberry Pi-based hardware. This means that for less than $250, one could build a single micro computer that will run both apps very well . For less than that, one could build a micro computer that favored one or the other. Their pricing structures (free to use, some cost when using services that cost the company) are reasonable and accessible. The availability of the new Apple M1 chip computers similarly means that more computing power is available for less money than ever before.

Of note, though they are both currently limited by Amazon’s AWS roll out schedule, most expect North American managed server solutions for SoundJack and JackTrip to reach a significant percentage of the population over the next two months. The advantages of using a server-based low latency solution include the ability to connect dozens of musicians simultaneously with less router tweaking and no need for a particularly powerful computer.

Other projects continue to develop. The most interesting one to me is the WebRTC-based LiveLab.app (chrome only), which just released a new audio solution that beats Zoom’s hi-fidelity music mode. It is more flexible than Zoom, runs in peer to peer mode, has about one third the latency and CPU footprint, and is free. As this project, and others like it continue to develop, music lessons should be able to leave the Zoom platform entirely.

None of this development would have taken place but for members of our community unwilling to let go of actual real-time interactions online. Their values demanded it, even if the initial results were not perfect. Even if it took more work. Even if it was hard.

Final Thoughts

Your values are shown in the things

that you refuse to do without.

Let this be the single most important lesson for the next pandemic: define your values early and set about living them out. Define that which you refuse to live without, even if it is hard. You will absolutely not meet your goals. But in repeatedly falling short over a long period of time, you will have moved the ball. You will have improved the lives of those around you. When the next pandemic comes, when we are once again shuttered and pulled apart in order to preserve life, remember what matters. Fight for it. If you are privileged enough to have resources and influence, fight for others. Fight because what you value matters.

And get vaccinated the absolute instant you can.